skip to main |

skip to sidebar

The most under-represented National League team in the 1952-1955 Red Man chewing tobacco card sets was the Chicago Cubs.

Despite there being 26 NLers issued each year, 1952-1953, and 25 each year, 1954-1955, only two of the 102 senior circuit cards were Chicago Cubs, and they were both issued in one year, 1953. The Cubs to be found on original Red Man cards are Hank Sauer and Warren Hacker.

My latest custom card is a latter-day attempt to balance that Chicago shortage. I've created a 1955 Red Man-style custom of Ernie Banks.

The '55RM Banks is only my second Red Man custom. A few years back I made a 1952 Red Man "rookie card" of Mickey Mantle. I've still got plans for at least 2-3 more Red Man customs. Watch this space for developments.

You can order this card. Unless otherwise noted, all of my custom cards are available to collectors for $12.50 each, postpaid for one or two cards; $9.95 each for three or more (mix/match). Complete checklists of all my custom baseball, football and non-sports custom cards were published on this blog in late May (baseball, football) and July 6 (non-sports). To order, email me at scbcguy@yahoo.com for directions on paying via check/money order, or to my PayPal account.

Uncommon commons: In more than 30 years in sportscards publishing I have thrown hundreds of notes into files about the players – usually non-star players – who made up the majority of the baseball and football cards I collected as a kid. Today, I keep adding to those files as I peruse microfilms of The Sporting News from the 1880s through the 1960s. I found these tidbits brought some life to the player pictures on those cards. I figure that if I enjoyed them, you might too.

Lately, I've been reading back issues of The Sporting News from 1957. I'm struck by how often racial issues were reported.

Big news at the time was the on-going Negro boycott of the New Orleans Pelicans and how it was contributing to that N.Y. Yankees farm team's last-place performance and uncertain future in the Southern Association (Class AA).

There were quite a few column inches in August of that year discussing whether opposing hitters were throwing at young Reds slugger Frank Robinson because he was black. (Minnie Minoso, a black Cuban, led the major leagues in being hit by pitch eight times between 1953-61.)

Frequently, the fact that this or that player was a Negro was mentioned, particularly young players who had been signed or promoted and whom the editors felt might not be well-known to readers.

One of the most troubling incidents in which race was the catalyst involved a carload of six members of the Tampa Tarpons, a Class D Florida State League affiliate of the Philadelphia Phillies and a group of shotgun-totting locals at Dade City, Fla. Whether the matter was an incipient lynching or just a handful of crackers having a little fun on a hot summer night is not knowable.

According to a SABR Baseball Bio project article on Tony Curry written by Rory Costello, the incident, which he described as "a sign of the times in the Deep South," unfolded thus.

Following a [Aug. 7 night] game at Leesburg, Tony was in a carful of Tarpons -- white, Latino, and black -- who stopped for milkshakes at a Dade City drive-in. Upon seeing the black passengers, a carhop asked them to move into the shadows, and “it was suggested they leave because there might be trouble.” African-American catcher Charlie Fields added, “Somebody had said something nasty.” As the ballplayers left, three shotgun blasts were fired, and one hit their car. They shook off a pursuing vehicle and went over the speed limit on purpose to attract the police of Zephyrhills. Luckily, there was just one minor injury, from birdshot pellets.

You can read Costello's complete article about Tony Curry at: Curry baseball bio .

In articles written in TSN by Ralph Warner, the six Tarpons were identified as three white players: pitcher Dick Colgan, catcher Vic Collier and shortstop Pete Torres, and three Negroes, Curry, an outfielder, catcher Charley Fields and outfielder Dario Rubensteing .

Warner wrote that "the white players went into the drive-in for food and were to bring out sandwiches to the three Negroes who remained in the car. The white players, while inside the cafe, were asked to move the car. {Editor's note: No doubt the car was initially parked in a spot where its Negro occupants could be to easily seen.] They complied and the firing occurred as the vehicle was pulling out."

The shots came from a group of men standing buy another car about 20 yards away.

Only one of the Tampa players was hit by the shotgun pellets. Colgan was struck four times in the right arm and shoulder. TSN described the injury as "flesh wounds," that were treated at a Zephyrhills hospital and later in Tampa.

Warner characterized the matter as an "isolated instance of racial trouble in the Florida State League." Tarpons manager Charlie Gassaway described the incident as "one of those unfortunate things that happen. I think the shooting was done by agitators."

It is difficult and probably unfair, to fall back on stereotypes in assessing the reaction of local law enforcement to the shooting. However, it took two weeks before arrests were made.

On Aug. 21, Pasco County Sheriff Leslie Bessenger. announced the arrests of four Dade City men, whom he described as a contractor, a bar operator, a packing plant worker and a mechanic. The contractor was charged with aggravated assault, the others as accessories. He said he had signed confessions from all four men and that the contractor had admitted he fired the shotgun. TSN did not name those charged.

Bond was set at $2,000 each, with a hearing set for Aug. 30.

It is open to speculation whether any arrests would have been forthcoming if Sheriff Bessenger's investigation had not been assisted by two agents of the Florida Sheriff's Bureau.

Bessenger was quoted, "This does not mean that I was making a half-hearted attempt to break the case. I believe that any hasty or spur-of-the-moment action on my part in a situation such as this would be more in keeping with the mob rule than with the thoroughness expected from an office such as mine. I keenly feel the reflection of such an incident on my office, on our town, our county and the state of Florida as a whole and intend to do all within my power to see that persons responsible are brought to justice."

If The Sporting News ever followed up on the story throughout the rest of 1957, I didn't see it. Whether the matter was an incipient lynching or just a handful of crackers having a little fun on a hot summer night is not knowable 60 years later.

Of the six Tampa players who caught fire that night in Dade City, only Tony Curry ever made the majors; most of the others never rose out of Class D.

Curry hit .253 over the 1960-61 seasons for the Phillies. After four seasons in the minors he returned to the bigs briefly with the Cleveland Indians in 1966.

Uncommon commons: In more than 30 years in sportscards publishing I have thrown hundreds of notes into files about the players – usually non-star players – who made up the majority of the baseball and football cards I collected as a kid. Today, I keep adding to those files as I peruse microfilms of The Sporting News from the 1880s through the 1960s. I found these tidbits brought some life to the player pictures on those cards. I figure that if I enjoyed them, you might too.

Dixie Walker had an 18-year major league career, most notably with the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World War II era, 1939-49.

He was a four-time All-Star and led the majors in batting with a .357 average in 1944 and in RBIs with 124 in 1945.

He was nicknamed "The Peoples' Cherce" by Dodgers fans.

But somewhere along the way he acquired a reputation among some opposing ballplayers and at least one writer as a "slug and run" cheap-shot artist.

The writer, Cy Kritzer, detailed the charges in a column in the Sept. 11, 1957 issue of The Sporting News.

Kriyzer was detailing the Sept. 4 fight between Walker, then managing the Toronto Maple Leafs, and Phil Cavarretta, skipper of the Buffalo Bisons. The teams had met in Toronto in a double-header, both games of which were won by Toronto, wresting first place in the International League from Buffalo.

I'll let Kritzer detail the action . . .

The Leafs had won the first game, 4 to 3, and were leading the second, 9 to 1, when Walker started a stormy protest at third base, accusing Bison third baseman Pete Castiglione of pinning down Bob Roselli before the Toronto backstop scored on a wild throw.

'Lou Ortiz, our captain was turning away when Walker swung at him,' said Phil. 'That's when I let Dixie have it. No one is going to swing at one of my players and get away with it, never.'

Walker dashed away from the scrap and wound up at second base in a headlock applied by Glenn Cox, Bisons' pitcher.

'I couldn't hit an old fellow like Dixie [he was 46 at the time],' said Cox, 'so I just let him quiet down.'

According to Kritzer, the only casualty was Bill Serena, a Buffalo reserve infielder, who suffered a "deep fingernail scratch" on his face when he knocked down Cavarretta in his charge to get to Walker.

Walker, Ortiz and Castiglione were expelled from the game for fighting. Kritzer reported that Toronto players did not join in the fighting, but were blocking Bison players to preserve order.

Kritzer then noted that an observer of the fracas was Chicago Cubs scout Lennie Merullo. In 1947, Merullo, then playing shortstop for the Cubs, was fined $1,000 for a pre-game fight with Walker in Ebbetts Field.

"That was another sneak punch and run-away by Walker, too," Kritzer quoted Cavarretta. "I was there, saw it all."

Cavarretta continued "There had been a fight the day before and someone punched Merullo when he was down. No one would tell him, but he suspected Pee Wee Reese.

"When he [Reese] went into the batting cage," Cavarretta went on, "Merullo followed him and demanded to know it it was Reese who punched him. While Pee Wee was disclaiming any guilt, Merullo was slugged from the rear.

"By Walker, of course. He was running to the Brooklyn dugout when Paul Erickson, a Chicago pitcher, tackled him. No fans were in the park because the gates had not been opened. The park police tried to take charge but both teams decided to form a ring and let Merullo and Dixie fight it out.

"Dixie lost two teeth and took a damn good licking before he cried 'That's enough.' This affair in Toronto reminded me of that one ten years ago. Dixie started this and deserved what he received."

Naturally, there was a rebuttal by Walker in the following week's paper.

"I never ran from a fight in my life and I don't intend to start now," Walker was quoted in an un-bylined artlcle, which included a different account of the 1947 Merullo-Walker fight.

The trouble began the previous night when Merullo had tangled with Dodgers second baseman Eddie Stanky.

The Sporting News issue of June 26, 1947, picked up the action, quoting Peanuts, then with the Cubs . . .

So the next day while Reese (Pee Wee) was in the cage taking his practice swings, Merullo sauntered by and called Pee Wee and uncomplimentary name, adding "And that goes for your whole so-and-so ball club."

With that, Dixie Walker punched Merullo on the side of the head and the boys were in business. Cavarretta, Merullo's roommate went after Walker but the big Cub pitcher, Paul Erickson, got there first.

He dragged Dixie over to a clear patch of ground, directed that Merullo be brought there, too, and then took charge of forming an arena. Players from both clubs made a big circle around them

I couldn't say who won the fight but they were both going at it real good. A little park cop broke through the ring, but Clyde McCullough grabbed him and tossed him right out again.

Finally a whole bunch of cops broke through and that was it.

Walker's version of the 1947 battle was also presented in the Sept. 18,1957, article . . .

Cavarretta jumped on my back when I was fighting Merullo and he had hold of me around the neck. I finally shucked him off, but he tore my shirt off. Then Erickson drove into my stomach with his shoulder, and I went over backwards, with his shoulder right into me. My shoulder felt like it was paralyzed. That's when I lost a tooth.

Walker continued, "But the thing that really burns me is for Cavarretta to say that I hit Merullo from behind, and then to say I ran."

Walker then revealed that after the fight with Merullo, then-Brooklyn general manager Branch Rickey called Walker into his office and rewarded him with a check for $1,000 for his "conduct over and above his duties as a ball player.

In 1957, playing under Walker, the Maple Leafs won their third International League pennant in four years.

Editor's note: This is an update to my blog post of June 2, 2009.

Editor's note: This is an update to my blog post of June 2, 2009.

From Pickles Dillhoefer and Austin McHenry in 1922 to Josh Hancock in 2007, the St. Louis Cardinals have, perhaps as much as any Major League Baseball team, suffered the untimely death of its players.

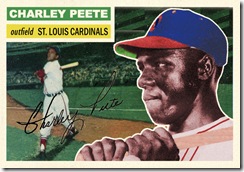

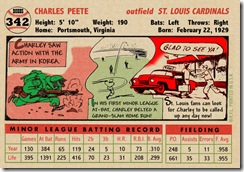

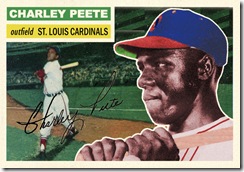

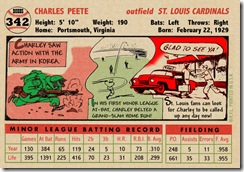

Probably none was more tragic and poignant than that of Charley Peete in late 1956, who died, along with his wife and three children, in a commercial airliner crash in South America.

Peete never appeared on a true baseball card in his short professional career, and on only a couple of collectibles as a minor leaguer. I recently made him the subject of one of my custom card creations, in the format of 1956 T opps. Besides showing you how the card turned out, I thought it appropriate to share Peete’s story with you.

Various contemporary sources give differing spellings of Peete’s name. An obituary in the local paper said that while an extra “e” was usually attached to his surname in the sports pages, the family said “Peet” was correct. Some sources give his informal name as Charlie, though he spelled it Charley when signing autographs, and used the Peete spelling on all known autographs, occasionally adding a “Jr.,” as his father’s name was also Charles. He was not known to have a middle name.

Peete claimed he was not a sports standout at Norcum High School in Portsmouth, Va., but he played baseball and football and ran track. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds and demonstrated an outstanding throwing arm.

Following high school, he played for various teams in Portsmouth’s competitive black semi-pro circuit. In 1950, at age 21, Charley played briefly with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League, then with his teenage brother Jimmy traveled from southeastern Virginia to participate in the inaugural season of the Manitoba-Dakota League, a professional circuit outside of Organized Baseball. Charley played for the Brandon Greys, whose 32-16 record was tops in the circuit, but who lost the league championship to the Winnipeg Buffaloes in the playoffs.

The ManDak League was notable for the number of Negro Leagues veterans who populated its rosters. Aging stars such as Leon Day, Ray Dandridge, Lyman Bostock Sr., and Willie Wells, Sr. and Jr. played there. The Minot Mallards even persuaded Satchel Paige to sign a three-game contract (at three innings per game), from whom leftie Jimmy Peete learned a thing or two about pitching as a teammate. Jimmy played in the minor leagues from 1955-59, reaching as high as the Pacific Coast League.

The Army reached out to Charley Peete after his season in Canada and he served in the Korean War. When he returned to civilian life in 1953, Charley petitioned Frank Lawrence, who owned the Portsmouth Merrimacs of the Class B Piedmont League, for a tryout. Peete had bulked up on army chow and at 190-200 pounds, had packed on such muscle that his teammates called him “Mule,” as in, “strong as a . . . .”

That strength was manifested in an outstanding throwing arm. One teammate said Peete could “hang blurred ropes” from right field, and that his throws “made a boiling, churning sound” as they went through the air.

Peete’s timing was good for his entry into Organized Baseball. In 1953 the Piedmont League, comprising teams in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, was in its first year of integration, with seven black players on four of its team as the season opened. Peete was given a uniform and began working out with the ’Macs. A few days later, he was called on to pinch-hit and in his first at-bat he hit a 3-2 pitch for a grand slam home run. He won the right field job and hit .275 for the season. For a brief 10-game period, one of Peete’s teammates on the ’Macs was Negro Leagues star and future Hall of Famer Buck Leonard, who was playing his only games in integrated Organized Baseball.

Peete followed up in 1954 by boosting his BA to .311 and his homerun output from four to 17. The Rochester Redwings, to the consternation of owner Merrimac’s owner Lawrence, an independent operator who had tried to sell Peete to St. Louis earlier that year, drafted Peete for what Lawrence termed a bargain price.

Peete made the jump from the Class B Piedmont League to the AAA International League for 1955. He was batting .280 for the Redwings after the first month of the minor league season, and the other St. Louis AAA farm club, the Omaha Cardinals of the American Association, purchased his contract to fill a vacancy in center field. The 1955 season was Omaha’s first at the Triple-A classification, the Cardinals having moved the team there from Columbus.

Charley ended the 1955 season at Omaha with a .317 BA, nine home runs and 63 RBI in 99 games. His combined batting record for Rochester and Omaha in 1955 was .310-10-73.

Peete appears in a very collectible team photo of the 1955 Omaha Cardinals. The Cardinals farm system in the early 1950s was, virtually across the board, prolific in its issue of team pictures and other collectibles. The ’55 Omaha picture is especially nice in that it is printed in rich, full color. The blank-backed, thin cardboard picture measures 6-3/4” x 4-3/4” and was, according to Dan Bretta, who supplied the scan illustrated herewith, a stadium giveaway.

Peete played winter ball in 1955 with Almendares in the Cuban League and Pastora in Venezuela’s Occidental League.

The 1956 season opened with Peete back in Omaha and hitting well enough that the Cardinals called him up on July 16. He arrived in St. Louis hampered by a split thumb and was able to hit only .192 with little power in 23 games over the month and a day that, as it developed, would comprise his entire major league career. Peete’s unorthodox batting style, which included dipping his bat as he swung, allowed big league pitchers to exploit his weakness on the low inside curve and he struck out in 10 of his 52 at-bats.

He was returned to Omaha and when he resumed his hot hitting and ended the season leading the Association with a .350 average, he was once again being touted as one of the Cardinals brightest prospects.

At Omaha in ’56 he was one of 22 O-Cards who appeared in a team-issue “PICTURE-PAK” that is actually a plastic comb-bound booklet of 3-1/2” x 4-3/8” facsimile autographed black-and-white photos. With the 1955 team photo, the picture pack is about the only remotely accessible Charley Peete memorabilia available to today’s collectors. A handful of Charley Peete autographs are known, but they are not inexpensive. One example on a 3x5 index card has been offered on an internet sales site for $1,600.

We’ll never know whether Charley Peete would have achieved major league stardom or his collectibles become ubiquitous because he didn’t live to see his 28th birthday. On Nov. 26 he boarded Linea Aeropostal Venezolana’s Flight 253 at Idlewild Airport in New York with his wife Nettie, age 21, their three young children (Deborah, 26 months, Karen, 15 months, and Kenny, not yet a month old), 13 other passengers and a crew of seven for an overnight flight to Caracas, where he was to join the Valencia team in the Venezuelan Association. Charley had begun the 1956-57 winter ball season with Cienfuegos in the Cuban League, but left after a few weeks.

Just after 8 a.m. on Nov. 27, the pilot of the Lockheed Constellation radioed that he was approaching Maiquetia, Caracas’ seaside airport in a rainstorm. He was two miles away. The plane never arrived; its charred wreckage was discovered later that day in cloud-shrouded 6,700-foot mountains nearby. There were no survivors. It was reported the bodies of the crash victims were buried the next day in Caracas. It is not known whether the Peete family’s remains were ever returned to their Portsmouth home.

A Little League field in Portsmouth is named for Charley Peete.

UPDATE: On Aug. 22, 1957, what The Sporting News described as an "elaborate bronze plaque" was permanently mounted on the wall of the stadium concourse. Peete's brother Jim, a pitcher for Reading (Eastern League) in the Cleveland organization, and Charley Peete's mother-in-law, Mrs. Odessa Davis, of Portsmouth, Va., attended the unveiling.

Since old Rosenblatt Stadium was demolished in 2010, I wonder where the plaque is today?

opps. Besides showing you how the card turned out, I thought it appropriate to share Peete’s story with you.

Various contemporary sources give differing spellings of Peete’s name. An obituary in the local paper said that while an extra “e” was usually attached to his surname in the sports pages, the family said “Peet” was correct. Some sources give his informal name as Charlie, though he spelled it Charley when signing autographs, and used the Peete spelling on all known autographs, occasionally adding a “Jr.,” as his father’s name was also Charles. He was not known to have a middle name.

Peete claimed he was not a sports standout at Norcum High School in Portsmouth, Va., but he played baseball and football and ran track. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds and demonstrated an outstanding throwing arm.

Following high school, he played for various teams in Portsmouth’s competitive black semi-pro circuit. In 1950, at age 21, Charley played briefly with the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League, then with his teenage brother Jimmy traveled from southeastern Virginia to participate in the inaugural season of the Manitoba-Dakota League, a professional circuit outside of Organized Baseball. Charley played for the Brandon Greys, whose 32-16 record was tops in the circuit, but who lost the league championship to the Winnipeg Buffaloes in the playoffs.

The ManDak League was notable for the number of Negro Leagues veterans who populated its rosters. Aging stars such as Leon Day, Ray Dandridge, Lyman Bostock Sr., and Willie Wells, Sr. and Jr. played there. The Minot Mallards even persuaded Satchel Paige to sign a three-game contract (at three innings per game), from whom leftie Jimmy Peete learned a thing or two about pitching as a teammate. Jimmy played in the minor leagues from 1955-59, reaching as high as the Pacific Coast League.

The Army reached out to Charley Peete after his season in Canada and he served in the Korean War. When he returned to civilian life in 1953, Charley petitioned Frank Lawrence, who owned the Portsmouth Merrimacs of the Class B Piedmont League, for a tryout. Peete had bulked up on army chow and at 190-200 pounds, had packed on such muscle that his teammates called him “Mule,” as in, “strong as a . . . .”

That strength was manifested in an outstanding throwing arm. One teammate said Peete could “hang blurred ropes” from right field, and that his throws “made a boiling, churning sound” as they went through the air.

Peete’s timing was good for his entry into Organized Baseball. In 1953 the Piedmont League, comprising teams in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, was in its first year of integration, with seven black players on four of its team as the season opened. Peete was given a uniform and began working out with the ’Macs. A few days later, he was called on to pinch-hit and in his first at-bat he hit a 3-2 pitch for a grand slam home run. He won the right field job and hit .275 for the season. For a brief 10-game period, one of Peete’s teammates on the ’Macs was Negro Leagues star and future Hall of Famer Buck Leonard, who was playing his only games in integrated Organized Baseball.

Peete followed up in 1954 by boosting his BA to .311 and his homerun output from four to 17. The Rochester Redwings, to the consternation of owner Merrimac’s owner Lawrence, an independent operator who had tried to sell Peete to St. Louis earlier that year, drafted Peete for what Lawrence termed a bargain price.

Peete made the jump from the Class B Piedmont League to the AAA International League for 1955. He was batting .280 for the Redwings after the first month of the minor league season, and the other St. Louis AAA farm club, the Omaha Cardinals of the American Association, purchased his contract to fill a vacancy in center field. The 1955 season was Omaha’s first at the Triple-A classification, the Cardinals having moved the team there from Columbus.

Charley ended the 1955 season at Omaha with a .317 BA, nine home runs and 63 RBI in 99 games. His combined batting record for Rochester and Omaha in 1955 was .310-10-73.

Peete appears in a very collectible team photo of the 1955 Omaha Cardinals. The Cardinals farm system in the early 1950s was, virtually across the board, prolific in its issue of team pictures and other collectibles. The ’55 Omaha picture is especially nice in that it is printed in rich, full color. The blank-backed, thin cardboard picture measures 6-3/4” x 4-3/4” and was, according to Dan Bretta, who supplied the scan illustrated herewith, a stadium giveaway.

Peete played winter ball in 1955 with Almendares in the Cuban League and Pastora in Venezuela’s Occidental League.

The 1956 season opened with Peete back in Omaha and hitting well enough that the Cardinals called him up on July 16. He arrived in St. Louis hampered by a split thumb and was able to hit only .192 with little power in 23 games over the month and a day that, as it developed, would comprise his entire major league career. Peete’s unorthodox batting style, which included dipping his bat as he swung, allowed big league pitchers to exploit his weakness on the low inside curve and he struck out in 10 of his 52 at-bats.

He was returned to Omaha and when he resumed his hot hitting and ended the season leading the Association with a .350 average, he was once again being touted as one of the Cardinals brightest prospects.

At Omaha in ’56 he was one of 22 O-Cards who appeared in a team-issue “PICTURE-PAK” that is actually a plastic comb-bound booklet of 3-1/2” x 4-3/8” facsimile autographed black-and-white photos. With the 1955 team photo, the picture pack is about the only remotely accessible Charley Peete memorabilia available to today’s collectors. A handful of Charley Peete autographs are known, but they are not inexpensive. One example on a 3x5 index card has been offered on an internet sales site for $1,600.

We’ll never know whether Charley Peete would have achieved major league stardom or his collectibles become ubiquitous because he didn’t live to see his 28th birthday. On Nov. 26 he boarded Linea Aeropostal Venezolana’s Flight 253 at Idlewild Airport in New York with his wife Nettie, age 21, their three young children (Deborah, 26 months, Karen, 15 months, and Kenny, not yet a month old), 13 other passengers and a crew of seven for an overnight flight to Caracas, where he was to join the Valencia team in the Venezuelan Association. Charley had begun the 1956-57 winter ball season with Cienfuegos in the Cuban League, but left after a few weeks.

Just after 8 a.m. on Nov. 27, the pilot of the Lockheed Constellation radioed that he was approaching Maiquetia, Caracas’ seaside airport in a rainstorm. He was two miles away. The plane never arrived; its charred wreckage was discovered later that day in cloud-shrouded 6,700-foot mountains nearby. There were no survivors. It was reported the bodies of the crash victims were buried the next day in Caracas. It is not known whether the Peete family’s remains were ever returned to their Portsmouth home.

A Little League field in Portsmouth is named for Charley Peete.

UPDATE: On Aug. 22, 1957, what The Sporting News described as an "elaborate bronze plaque" was permanently mounted on the wall of the stadium concourse. Peete's brother Jim, a pitcher for Reading (Eastern League) in the Cleveland organization, and Charley Peete's mother-in-law, Mrs. Odessa Davis, of Portsmouth, Va., attended the unveiling.

Since old Rosenblatt Stadium was demolished in 2010, I wonder where the plaque is today?

Uncommon commons: In more than 30 years in sportscards publishing I have thrown hundreds of notes into files about the players – usually non-star players – who made up the majority of the baseball and football cards I collected as a kid. Today, I keep adding to those files as I peruse microfilms of The Sporting News from the 1880s through the 1960s. I found these tidbits brought some life to the player pictures on those cards. I figure that if I enjoyed them, you might too.

I never would have guessed that 11 years after Jackie Robinson broke the modern major league color barrier, that the baseball media was still keeping track of such things . . . but did you ever wonder who was the first black major leaguer to throw the first punch in a major league on-field fight?

All of the books, movies, tv shows, etc., about Robinson played up the agreement he made with Branch Rickey to keep his cool when things got hot. I don't know if he ever threw the first punch in baseball fight.

Reading a late-June, 1957, issue of The Sporting News, it appears that Larry Doby, then with the Chicago White Sox, may have been the first black major leaguer to throw the first punch in a rhubarb. The historic moment in baseball race relations came June 13, 1957, at Comiskey Park.

That's according to an article by Shirley Povich of the Washington Post & Times Herald. According to the writer, Doby threw the first punch at Yankees pitcher Art Ditmar, connecting with a "left hook" that flattened Ditmar.

Only seconds earlier, Doby had been flat on his back, having avoided a high inside fast ball from Ditmar in what Povich called a "dust-off situation" where the pitcher could afford to waste a pitch.

In the bottom of the 1st inning, there were two White Sox on base; Nellie Fox having walked and Minnie Minoso having singled. Two were out. Ditmar uncorked a wild pitch that came too close to Doby's head. When the Yankees pitcher ran in to cover the plate, he and Doby "traded insults" and Doby decked Ditmar.

Predictably, the benches cleared. When the brawl was over, Doby, Walt Dropo and Billy Martin had been thrown out of the game. Enos Slaughter, who was not in the Yankees lineup that game, was removed from the bench. Ditmar was allowed to remain in the game because he had not been the aggressor . . . aside from that bean ball thing.

Because American League president Will Harridge was in attendance at the game, assessments against the combatants came swiftly. Doby, Slaughter and Martin were fined $150 each; Dropo and Ditmar were plastered for $100 each.

After the game, Yankees owner Dan Topping said the team would pay the fines on Martin, Slaughter and Ditmar. Harridge had to remind him that was illegal according to AL rules.

Neither Fox nor Minoso had scored during the melee and the Yankees ended up winning the game 4-3.

As is often case in such incidents, there had been recent bad blood between the teams. The White Sox had won the previous night's game 7-6, increasing their lead in the AL to five games over the second-lace Yankees.

In that game, Yankees pitcher Al Cicotte had twice flipped Minnie Minoso and as the two teams were returning to their clubhouses after the game via a shared ramp, Minoso had to be restrained from going after Cicotte.

Doby never got a hit off Ditmar in 1957, striking out in three of his eight at-bats against him.